Confronting Preterism’s Roots:

A Jesuit Counter-Reformation Strategy in Modern Protestant Garb Introduction

Modern Christian eschatology is a landscape of divergent systems, with futurism, historicism, idealism, and preterism each vying for scriptural credibility. Among these, preterism—the belief that most or all biblical prophecies, particularly in Revelation and the Olivet Discourse, were fulfilled in the first century—has gained increasing traction among certain conservative Protestants, especially within the Reformed tradition. Advocates like R.C. Sproul, Kenneth Gentry, and Gary DeMar have helped popularize a form of “partial preterism” which teaches that the destruction of Jerusalem in A.D. 70 was the fulfillment of much of Jesus’ prophetic discourse, and possibly Revelation itself.

However, what is often left unacknowledged is the origin of preterism in the Counter-Reformation, developed not as a neutral theological system, but as an intentional apologetic maneuver by a Jesuit priest— Luis de Alcázar—to shield the Roman Catholic Church from the charge of being the Antichrist. Recognizing this historical context should give modern non-Catholic preterists pause. Can a theological system born as a defense of the Papacy now serve as a reliable lens for interpreting prophecy within Protestantism?

Luis de Alcázar and the Birth of Preterism

Luis de Alcázar (1554–1613), a Spanish Jesuit and theologian, lived and worked during the height of the Catholic Counter-Reformation—the Church’s organized response to the Protestant Reformation. During this period, the Papacy faced relentless accusations from Reformers such as Luther, Calvin, and Knox, all of whom identified the Pope as the Antichrist and the Roman Church as the Babylon of Revelation. This interpretation was central to the historicist framework adopted by Protestants, which saw prophecy as unfolding throughout church history, with the Roman Catholic Church playing a prominent role in opposition to Christ.

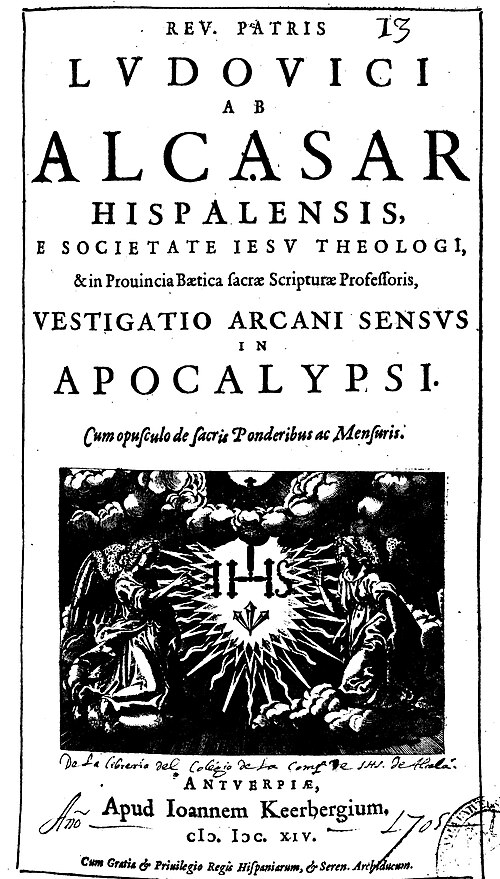

In this context, Alcázar composed his magnum opus, Vestigatio Arcani Sensus in Apocalypsi (published posthumously in 1614), a massive commentary on the book of Revelation. His key thesis was that Revelation does not concern the distant future, nor the corruptions of the medieval church, but rather was fulfilled almost entirely in the early centuries of Christianity. He argued that the prophecies referred to:

The persecution of Christians under pagan Rome,

The fall of Jerusalem in A.D. 70,

The triumph of the Church over her early enemies.

This radical reinterpretation had a clear purpose: to exonerate the Roman Church from the accusations of the Reformers by recasting Revelation as a closed book, already fulfilled and thus irrelevant to the contemporary church. Alcázar’s preterism was not developed in theological isolation or dispassionate study—it was deeply political, crafted to neutralize Protestant polemics and defend the authority of the Papacy.

The Jesuit Context and Counter-Reformation Strategy

To understand Alcázar’s motivations, one must understand the role of the Jesuits in the Counter-Reformation. Founded in 1540 by Ignatius of Loyola, the Society of Jesus was tasked with confronting Protestantism intellectually, politically, and spiritually. Jesuits became the vanguard of Rome’s theological offensive, producing scholars who would reinterpret Scripture in ways that advanced Catholic interests.

In this environment, Alcázar’s approach offered a powerful tool: reinterpret the prophecies not as future threats to ecclesiastical power, but as past events that vindicated the Church’s origins and historical mission. This strategy allowed Catholic theologians to answer Protestant charges with academic sophistication while redirecting the focus of Revelation away from Rome’s abuses and onto the Roman Empire of antiquity.

Matthew 16:28 — A Test Case in Interpretive Divergence

One key verse that reveals the contrast between Alcázar’s approach and traditional or premillennial views is Matthew 16:28, where Jesus declares:

“Verily I say unto you, There be some standing here, which shall not taste of death, till they see the Son of man coming in his kingdom.” (KJV)

Alcázar and modern preterists interpret this verse as referring to the destruction of Jerusalem in A.D. 70, asserting that this event was the “coming of the Son of Man in judgment.” They argue that Christ came spiritually and symbolically to end the old covenant order.

However, early church fathers, such as Irenaeus and Hippolytus, and many modern premillennialists, interpret this as referring to either:

The Transfiguration (a foretaste of kingdom glory witnessed by Peter, James, and John),

Or a reference to the Second Coming, with “some” possibly referring to John living long enough to receive the vision of Christ in Revelation.

Premillennialists reject the idea that A.D. 70 fulfilled Christ’s return, since the actual return is bodily, visible, and cosmic, as described in Acts 1:11 and Revelation 19. They hold that the kingdom’s full manifestation is still future, involving Christ’s reign on earth. In this way, Alcázar’s interpretation significantly redefines the nature and timing of Christ’s return, spiritualizing what the early church and historic premillennialists took literally and future.

Modern Protestant Adoption of Preterism

Ironically, the seeds planted by Alcázar have sprouted in modern conservative Protestant circles, particularly among Reformed theologians seeking to make sense of eschatology in a post Enlightenment age. Frustrated by sensationalist dispensationalism and attracted to covenantal themes, many have turned to preterism— especially partial preterism—as a more scholarly and historically grounded alternative.

They argue that:

Jesus’ prophecies in Matthew 24, Mark 13, and Luke 21 were fulfilled in A.D. 70.

The tribulation and judgment referred to the end of the Jewish age, not a future global apocalypse.

Revelation (or most of it) describes first-century events like Nero’s persecution, the fall of Jerusalem, and the vindication of the Church.

While this system may appeal to the Reformed mind due to its textual nuance and historical grounding, it must be acknowledged that it shares a theological DNA with Counter-Reformation Romanism, designed to protect the very institution the Reformers protested.

A Call for Discernment

Modern Protestants who adopt preterism—especially those who claim to be faithful to the Reformation—must wrestle with this uncomfortable reality. Can one claim to be historically aligned with Luther, Calvin, or Knox while employing an interpretive method crafted to refute them? Should a system invented to defend the Papacy now guide the Church in understanding prophecy?

Furthermore, preterism’s implications can be troubling:

It diminishes the relevance of Christ’s return as a future, bodily hope.

It often blurs the lines between Israel and the Church, leading to replacement theology.

It can lead to theological complacency, as prophecy is viewed as “already fulfilled” and no longer an urgent motivator for mission, warning, or vigilance.

Even partial preterists, who still affirm a future Second Coming, must admit that their system depends heavily on Alcázar’s groundwork, even if stripped of its Catholic polemics.

Conclusion

Preterism did not arise from the fertile soil of Protestant exegesis or early Christian consensus—it was born in the crucible of religious warfare, forged by a Jesuit hand to shield the Roman Church from condemnation. While today’s preterists may approach the system with sincere intentions and theological rigor, they cannot escape the historical origins of the method they use.

To remain faithful to the principles of sola Scriptura and the historic Protestant testimony, the Church must examine not only what a system teaches, but also why it was developed and who first wielded it. In the case of preterism, that path leads not to Geneva, Wittenberg, or the early church—but to Seville, to Jesuit scholars, and to the defenders of Rome.