A Defense of the King James Translators Against Modern Criticism

By Lacy Evans

June 28, 2025

Defending the Scholarly Excellence and Reverence of the King James Bible Translators

In today’s landscape of biblical: scholarship and preaching, it is not uncommon to hear modern ministers, armed with a semester or two of Greek or Hebrew, stand confidently at the pulpit and correct the venerable King James Version (KJV) of the Bible. This phenomenon, though often well-intentioned, reveals a degree of presumptuousness and ignorance that can be as audacious as it is misguided. To truly appreciate the magnitude of the KJV translators’ work, one must understand the profound scholarship, the rigorous methodology, and the deep spiritual reverence that characterized their efforts—qualities that remain largely unmatched by many modern critics.

The King James Bible, completed in 1611, was the fruit of a monumental scholarly endeavor commissioned by King James I of England. The translation project brought together nearly fifty of the most learned divines and linguists of the time, selected specifically for their expertise in the original biblical languages —Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek—as well as Latin and other tongues. These men were not casual students of Scripture; they were seasoned scholars, theologians, and church leaders, chosen with great care to produce a translation both accurate and reverent.

The Qualifications of the Translators: Giants of Sacred Scholarship

To call the King James translators “qualified” is something of an understatement. These men represented the academic elite of early 17th-century England —products of Oxford, Cambridge, and other premier institutions—many of whom held multiple advanced degrees and were fluent in numerous ancient and modern languages.

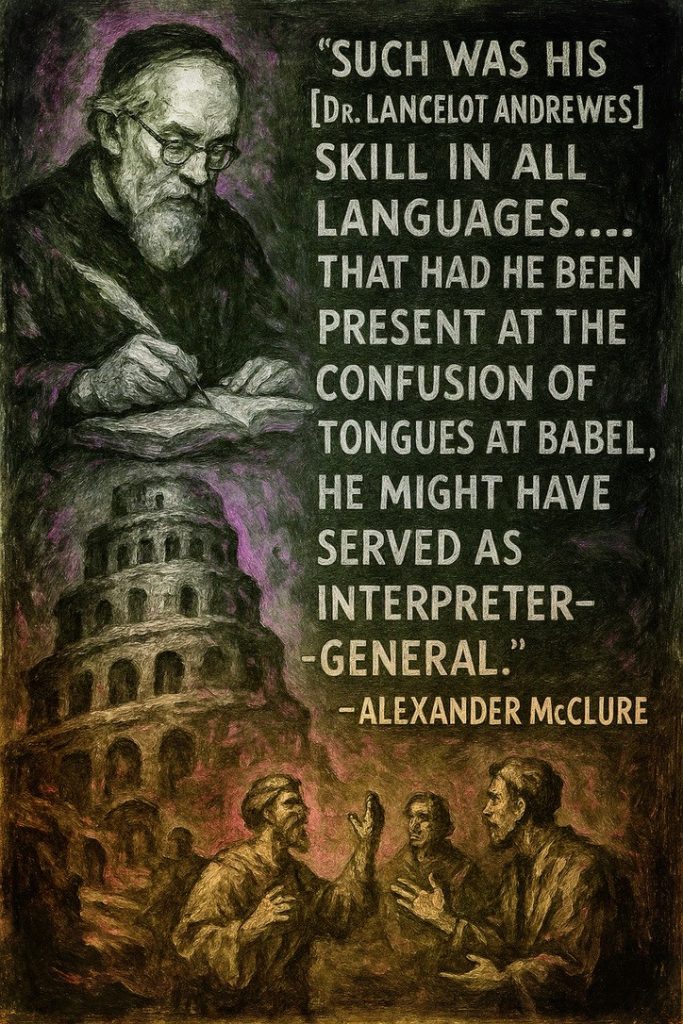

Take, for example, Dr. Lancelot Andrewes, the director of the First Westminster Company, responsible for translating the early books of the Old Testament. Andrewes reportedly spoke at least fifteen languages fluently, including Hebrew, Greek, Latin, Chaldee, Syriac, Arabic, and several European languages. The famed scholar Hugo Grotius once remarked that Andrewes was

“The most learned man in the world.”

Alexander McClure agrees, “Such was his skill in all languages… that had he been present at the confusion of tongues at Babel, he might have served as interpreter-general.”

Another standout was Dr. Miles Smith, a key contributor and one of the final editors of the KJV. He was deeply read in the early church fathers, rabbinical literature, and Hebrew customs. Fluent in Chaldee, Syriac, and Arabic, Smith wrote the preface to the 1611 edition, The Translators to the Reader, a masterful and humble defense of the translators’ work and purpose.

Dr. John Rainolds, head of the Puritan delegation at the Hampton Court Conference, was a brilliant Hebraist and theologian. His insistence on a new translation helped launch the entire project. Rainolds was said to be so well-read that when one clergyman called him “a living library,” no one objected.

Even lesser-known contributors like George Abbot and Richard Brett brought extraordinary depth to the translation teams.

But their strength was not just in individual brilliance. It was the collective intellectual force of these men—combined with their humility before the text—that made their work exceptional. Their qualifications were not merely cumulative, but exponential, as each scholar’s strength sharpened the others through careful review and spirited, respectful discourse.

A Work of Sacred Collaboration: Checks, Balances, and Reverence

The process of translation was not haphazard nor left to individual opinion. The King James Bible was crafted through a system of six translation companies divided between Westminster, Oxford, and Cambridge. Each company was assigned a portion of Scripture, and each member translated every verse independently before the group met to compare and refine the translation. Once a section was agreed upon, it was sent to other companies for review. If any dispute arose over a word or phrase, it was debated—often fiercely but respectfully —until a consensus was reached.

This created multiple layers of review and accountability, a system of internal checks and balances rare in translation projects then or now. Rather than relying on a single editor or committee with shared bias, the KJV translation process distributed responsibility among diverse scholarly minds and theological perspectives—Puritan, Anglican, and others— ensuring that no single faction dominated the outcome.

Equally vital was their spiritual posture. The translators were not merely academics or linguists; they were men of prayer, committed to the authority and sanctity of Scripture. In the Translators to the Reader, Miles Smith wrote that they approached the work “not to make a new translation, nor yet to make of a bad one a good one…but to make a good one better.” They were well aware of the solemnity of handling the Word of

God and undertook the task with what Smith called “fear and trembling.”

This reverence is notably absent in much of modern textual criticism, which often treats the Scriptures more as ancient artifacts than as living oracles.

The Modern Critic: Presumptuousness Cloaked in Greek (“Megalos-tic” Mistakes)

In sharp contrast to the humility and reverence of the KJV translators stands a growing trend in modern pulpits and seminaries: ministers with a passing familiarity with Greek or Hebrew boldly correcting the King James Bible, often with an air of scholarly superiority that far exceeds their actual training.

Here’s a humorous but all-too-true example:

A preacher comes across the word “big” in the King James Bible. With theatrical confidence, he declares: “Now that word ‘big’ in the KJV is really the Greek word megalos! So when you go back to the original Greek, you find that this word means ‘not small,’ ‘of greater mass,’ ‘of greater relative size,’ etc. You see, in order to really understand the word, you have to know the original language.”

What this illustrates—beyond the comedy—is the danger of superficial knowledge dressed up as authority. The preacher is not adding any real insight; he is essentially repeating what the English already communicates, only now in Greek, to the applause of those who don’t know better. It’s the theological equivalent of putting a mustache on the Mona Lisa and calling it a restoration.

This kind of presumptuous correction fails to reckon with the staggering depth of understanding possessed by the original translators.

Presumption and the Loss of Reverence

To critique is not inherently wrong. Even the KJV translators acknowledged the imperfections of all human work. But what we so often see today is not critique rooted in deep reverence and careful scholarship—it is presumption cloaked in sophistication, a spirit of correction untethered from humility.

In past centuries, the handling of the Scriptures was approached with sacred awe. To touch the Word was to approach holy ground. Today, too many handle it like a casual blog post, confidently reshaping it with little fear that they might err against God Himself. The translator’s chair has become, in some circles, a stage for self-expression, rather than a seat of sacred responsibility.

This is not merely an academic misstep—it is a spiritual one. To correct what one has not deeply understood is not courage; it is arrogance. And to assume that one’s limited training outweighs the corporate wisdom of fifty men whose lives were bathed in prayer, study, and sacrifice is not scholarly integrity—it is audacity born of ignorance.

The words of Proverbs ring loudly here: “Seest thou a man wise in his own conceit? There is more hope of a fool than of him.” (Proverbs 26:12)

A Legacy That Endures

More than four centuries have passed since the King James Bible was first published in 1611, and yet it remains one of the most widely read, quoted, and loved translations of Scripture in the English-speaking world. Its influence on theology, literature, language, and worship is incalculable.

This is no accident. The translators labored not for novelty, but for faithfulness. Not for fame, but for fidelity to God’s Word. They believed, as we should, that the Scriptures were not to be trifled with or editorialized at whim—but handled with fear and trembling, line upon line, precept upon precept.

Their legacy reminds us that truth and beauty are not enemies. That scholarship can live hand-in-hand with reverence. And that when men of godly character come together with humble hearts, rigorous minds, and a shared love for God’s Word, the result can be something truly enduring.

In Closing

It is the height of folly for modern preachers and critics—with limited training and a casual posture—to rise in judgment over a translation crafted by men whose intellectual and spiritual qualifications eclipse their own many times over.

To stand atop a molehill and scoff at the mountain is not courage. It is blindness.

Let us be careful not to let superficial knowledge breed superficial reverence. Let us remember that the King James Bible was born of sacred scholarship, reverent collaboration, and a fear of God too often absent in today’s textual debates.

And the next time a preacher confidently “corrects” the KJV with a Greek word like megalos, may we remember: sometimes, the wisest man in the room is the one who knows how much he has yet to learn.